John Truby: The Anatomy of Story

If you’re anything like me, you’ve probably got a story to tell.

Maybe you’ve lived through something difficult, interesting, or unique, and you’re determined to share your experience and wisdom to help others going through something similar.

Perhaps friends have even encouraged you to write it.

You should write a book, they say. You’re such a good writer.

I started hearing this not long after my husband, Dennis, died of brain cancer at the age of 44, leaving me to raise our nine- and eleven-year-olds alone. I even had a head start: 15,000 words I’d originally written on CaringBridge while he was sick. Some of the folks who’d followed our journey by reading along on that blog were encouraging me to publish the blog posts as a book.

But here’s the problem: I knew I had the start of a book. I had thousands of words documenting, in real-time, a young family’s experience facing terminal illness, which felt like a good place to begin. But I also knew it wasn’t a book yet.

I had no idea what would make it a book, however. I just had a sense that it couldn’t be merely a recitation of events: “This happened…this happened…this happened…The End.”

It wasn’t until I came across John Truby’s book, The Anatomy of Story, that I learned about the importance of story arc and character development in memoir. An interesting — and challenging — aspect of memoir that I didn’t fully appreciate until I began writing my own was that a memoir needs many of the compelling elements that go into a good fiction story. But, of course, you’re constrained by the truth. You can’t just make up an ally or opponent to interact with the hero (you). You can’t invent plot points to advance the story.

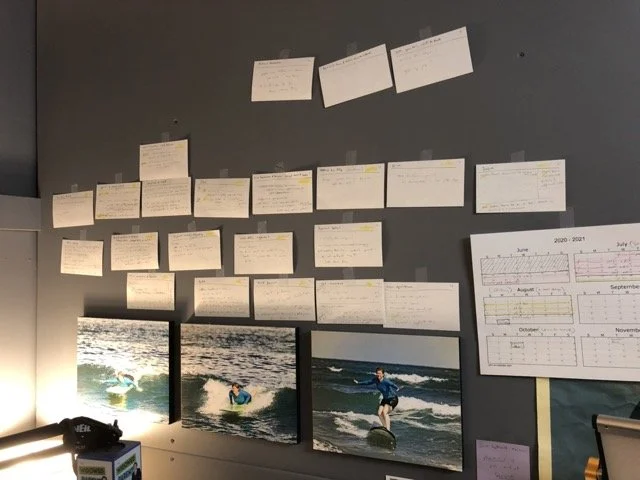

Events and characters from my memoir mapped onto notecards on the wall above my computer

After my manuscript was partially drafted, I was struggling to figure out where there were holes and, perhaps most importantly, where the story should end. That’s when I stumbled across Truby’s book. I put my writing aside and dove into studying his lessons and examples. I learned about inciting events, story worlds, the hero’s weakness and need that would drive the story, and so much more.

I studied his character types; it was easy to identify who the allies in my story were, but I’d never heard of, for example, the “fake-ally opponent.” (I decided it was the hospice chaplain who tried to dissuade me from speaking at the funeral.)

I mapped all of the key story elements and characters onto notecards and set about trying to map them to the events and people in my manuscript. I taped them on the wall above my computer. I moved them around. I scratched things out. I dove back into my manuscript with an eye toward the notecards to ensure that I had covered all the critical elements in the story.

I also learned from Truby’s book about the importance of the opening line and how you can use it to encapsulate the themes in the book. I spent hours staring at the ceiling working on that single first sentence, so I was especially thrilled to win an award from Zibby Books for it.

If you’re writing a memoir, or have dreams of writing one, I encourage you to pick up The Anatomy of Story. It’s not a quick read. It’s filled with detailed examples from literature and film which helped me understand the important story elements and gaps in my memoir.

Of course, you’ll want to work with a professional editor, too. They can help with these story-level “developmental editing” questions, and much more. But I always like to have my manuscript in the best shape I can, on my own, before I turn it over to my editor. Once I finally decide that I’m sick of it and I can’t possibly look at it one more time, that’s when I know it’s time to turn it over to her.

I hope you find John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story helpful as you work on your memoir.

Next Steps

DOWNLOAD: 10 Questions to Ask an Editor

Does someone you know need this blog?

Here is the sign-up page.

[ Free Learning: Crash Course for Nonfiction Authors ]